Note: This is a collaborative effort with Hooman, of course, although as the "host" in this exercise it was my task to do the actual writing.

I've chosen not to italicize ships names in the article, as it would probably take me hours to do so.

*********

From "Jones' Quaterly Naval Review", Summer 1925 edition:

The annual SAINT naval exercises have concluded following almost two weeks of intense activity between Ceylon and Minicoy Island.

As India was hosting, it fell to the Bharatiya Nau Sena to determine the scope of the exercises. This time, it was decided that the Royal South African Navy would be tasked with “attacking” the Indian base at Columbo. After some discussion about where to base the RSAN force during the exercises, it was agreed that Minicoy Island would be the South African base. Minicoy’s small depot had little to offer the RSAN, which was the point - the exercise would test the Fleet Train’s ability to set up a forward operating base to support combat operations.

The RSAN contingent consisted of:

1st Battle Squadron, 1st Division: BB South Africa (Flag), Cameroon

1st Cruiser Squadron, 2nd Division: CL Kimberly, Welkom

5th Cruiser Squadron, 1st Division: CL Libreville, Maroua

Experimental Flotilla: CVX Wim Kraash

3rd Scout Squadron (A), 1st (Half-)Division: AV Mimir

1st Destroyer Flotilla, 1st Division: DD Agaue, Aktaia, Amphitrite, Autonoe

1st Destroyer Flotilla, 2nd Division: DD Doris, Doto, Dynamene, Eione

Fleet Train: FO Marie Celeste, TD Mossel Bay, RS Escartian

Meanwhile, the Indian force, drawn largely from the Central Maritime District, consisted of:

Battle Squadron: BB Dara Shikoh (flag), Babur

1st Naval Aviation Squadron: CVL Otta

1st Cruiser Squadron: CA Male, CL Lucknow

5th Cruiser Squadron: CL Goa, Port Blair, Jaipur

1st Destroyer Squadron: DD G-114, G-115, G-116, G-120, G-121

7th Destroyer Squadron: DD G-129, G-130, G-131, G-132

2nd Escort Squadron: SL S-101, S-102, S-106

1st Submarine Squadron: SS I-2, I-3, I-4

2nd Coastal Patrol Squadron: 12 MTB

Some land-based aircraft, including two AA-3 medium bombers, were also included in the Indian order of battle.

Unlike previous years, there were no rules intended to put the Indian battleships on an equal footing with their South African counterparts. Part of the problem was thus that the Indian battleline was badly outclassed by the South African battleline; it would be up to the Indians to use other options - submarines, coastal forces, aircraft - to overcome this obstacle.

As the exercises began, neither side knew a great deal about each other, apart from the capital ships and aircraft carriers involved. This was also a change, for it had been noticed in previous exercises that sailors in both navies that having the opposition’s OOB in hand did make identification a little too easy.

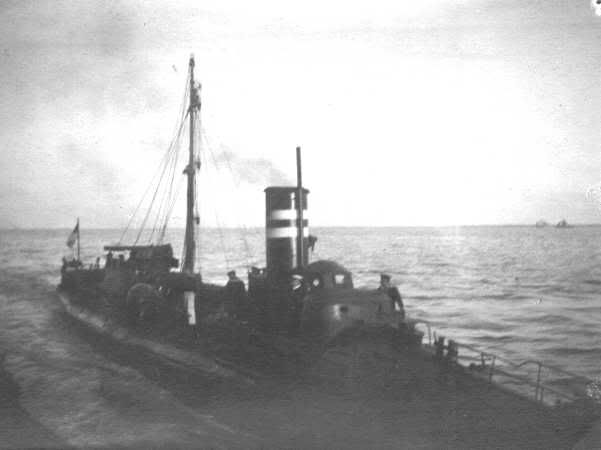

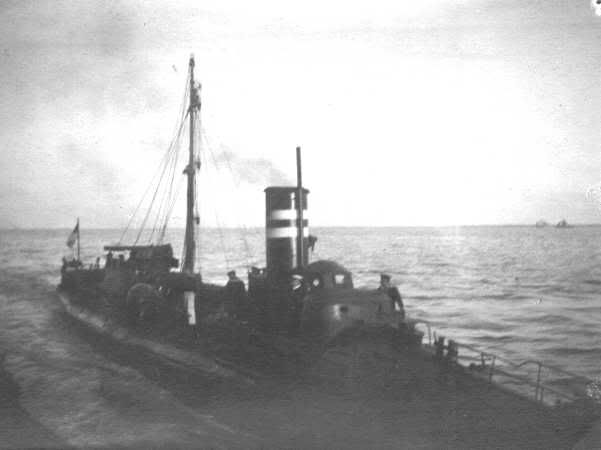

Above: an Indian dispatch boat comes along side to transfer referees aboard RSAN South Africa (Credit for all photos: Royal South African Naval Photographic Archive)

Above: an Indian dispatch boat comes along side to transfer referees aboard RSAN South Africa (Credit for all photos: Royal South African Naval Photographic Archive)

Thus there was some wariness on both sides - the South Africans were unsure what light forces were at hand, and the Indians spent some time looking for one or more new heavy cruisers in the RSAN fleet. This was a futile effort, as there were none.

11 May

A day of reconnaissance. Both sides used aircraft in an attempt to determine the other’s order of battle. Success is limited.

12 May

Rear-Admiral Falkenburg decided to strike hard and fast, surging his battleline straight at Ceylon. Wim Kraash and its escorts trailed behind, moving at fifteen knots and providing what air cover it can to the battleline.

The Indians were still positioning their submarines, and Rear-Admiral Muivah was holding his surface forces at Columbo, awaiting a spotting report from his aircraft. No such report would be forthcoming that day.

13 May

The RSAN force struck fast and aggressively, arriving off Columbo at 1015. Rear-Admiral Muivah was drawn out from under Columbo’s guns, leaving him in a bad situation. At 1050, Dara Shikoh was ruled to be sinking, leaving Babur to face both RSAN dreadnoughts. Her destruction was not far behind, officially noted at 1123. Though both sides lost cruisers and destroyers, the South African battleships were virtually unscathed, having used their larger guns and superior speed to control the battle.

The RSAN moved into engage Columbo at noon, and although there was some fire traded with the shore batteries, the attackers achieved their objectives and destroyed the naval base. Referees called the battle at 1442, and the South Africans headed back for Minicoy.

14 May

The South Africans returned to Minicoy late in the evening, and took on additional fuel and supplies.

Meanwhile, Rear-Admiral Muivah held a staff meeting to assess his force’s rather severe defeat. Captain Baru, of the carrier Otta, convinced Muivah to cut him loose; a plan was crafted and Otta sailed with a meagre escort that evening.

15 May

The second round was a much different story. At 0900, just two hours after departing Minicoy, the RSAN force was sighted by a land-based AA-3 medium bomber. This information was reported back to Rear-Admiral Muivah and then to Otta.

At 1220, the South Africans found themselves under aerial attack as Otta flung six fighters and all twelve of her scout-bombers at the RSAN squadron. At a cost of a fighter and two scout-bombers, the Indians succeeded in striking their target - the CVL Wim Kraash. Wim Krassh was ruled to be hit by three fifty kilogram bombs, creating three holes in the flight deck and starting a fire in the hanger, where one bomb was judged to have hit an avgas line.

Leaving the stricken carrier behind with a single destroyer, the RSAN pressed forward, enduring a second attack by Otta’s airgroup at 1940. Attacking out of the low evening sun, the Indians pressed the attack on two ships - the cruisers Welkom and Libreville. Libreville was hit twice and strafed repeatedly, while Welkom avoided being bomb hits, though the Indians strafed her as well. Though two fighters and a scout-bomber were ruled shot down, the two cruisers had suffered a couple dozen casualties to exposed crewmen and some damage to light weapons, searchlights, and other unprotected equipment. The Indian success was marred by the genuine loss of a Baagh fighter, which stalled and crashed while attempting to land on Otta. Despite quick action by the destroyer in the plane guard position, the pilot was lost.

During the evening, chaos broke out as the submarine I-3 was detected on surface by the Aktaia while attempting a run in on the South Africa. I-3 fired a flare in the direction of the RSAN force before crash-diving. As the flare signalled the launch of torpedoes in that direction, the South Africans took evasive action while Aktaia and her sister Amphitrite make multiple depth-charging attacks. Eventually, after a harrowing two hours, the referee aboard I-3 ordered her to surface, where the sub informed the destroyers by signal lamp that she had been sunk.

16 May

At 0920, two AA-3 medium bombers attacked the RSAN fleet train at Minicoy Island. A floatplane from the Mimir engaged the bombers, damaging one and being damaged in turn. Nonetheless, the bombers pressed on and scored two hits, one each on Marie Celeste and Mossel Bay. The Fleet Train thus found itself in the unexpected position of defending itself from attack, and conducting damage control operations afterward.

At 1029, Otta’s exhausted airgroup - now down to nine fighters and nine scout-bombers, the genuinely lost fighter from yesterday being deemed a combat loss from the evening strike - attacked a third time. Once again, the aircraft concentrated on a cruiser, the Kimberley, hitting her twice and strafing her. Two fighters and two scout-bombers were shot down.

As the South Africans approached Columbo, the Indian battlegroup came out. Once again, the Indian battleships began taking the worst of the engagement, with Dara Shikoh suffering in particular. However, the Indian’s aerial tactics did pay off somewhat, as South African cruisers - three of them damaged to some degree - and their seven destroyers found themselves facing a massed charge by all five Indian cruisers, nine destroyers, and eleven motor-torpedo boats. As the two forces met, the engagement became very confused, with the Male nearly colliding with the Doris at one point. The South Africans let loose with their torpedoes, while the Indians conserved theirs for the battleships.

In short order, Male, Goa, three destroyers, and four MTBs were judged out of action, while Kimberly, Welkom, and three destroyers suffered a similar fate for the South Africans. While in reality some would undoubtedly have been sunk, there was more instructive value in the referees aboard each ship submitting the crews to strenuous damage control exercises for the remainder of the battle.

With the cruiser Lucknow leading, the remaining Indian ships hurtled themselves at the South African battleships, which had turned to bring their broadsides to bear on the smaller foes. Lucknow and Port Blair were quickly disabled, but Jaipur, three destroyers, and five MTBs managed to launch their torpedoes. With about twenty torpedoes in the water, it was not surprising that three hit: two on the Cameroon, the other on the South Africa. The flagship was not heavily damaged, but Cameroon’s crew found itself dealing with a list and sufficient flooding to slow the ship to eighteen knots, as the referees gleefully unleashed a stiff regime of damage control drills upon her.

At 1430, the South Africans broke off, have failed to shell Columbo, but still having dealt out tremendous punishment to the defending forces. The only major Indian vessels ruled afloat afterward were Babur and Jaipur. However, the South Africans didn’t return to Minicoy Island unmolested. The submarine I-2 had positioned itself just ten kilometres south of the island, and surfaced in the midst of the formation to signal that had fired torpedoes at the Cameroon. The South African battleship was ruled to be sunk, though I-2 wasn’t long in following her. Round two was concluded at 2100, and the rosters were re-set.

Above: the I-2 on surface after being "sunk" by the RSAN.

Above: the I-2 on surface after being "sunk" by the RSAN.

17 May

Once again, a day of rest and replenishment.

18 May

As the third round began, the South Africans tried a new tactic. Wim Kraash, Welkom, and two destroyers headed for Ceylon, seeking out the Indian defenders, while the faster battlegroup sped south. Their course would ideally take them in a wide loop around the coast, allowing them to hit Ceylon from the south.

Around 1830, Wim Kraash’s aircraft spotted a formation of Indian cruisers and destroyers steaming in the direction of Minicoy. The South African carrier and escorts changed course to avoid contact, and plans were made for a morning strike - there was not enough daylight left to prep, launch, and recover a strike that evening.

As it turned out, four Indian cruisers and six destroyers were indeed at sea, seeking a night engagement with the South Africans, but they did’t make contact.

Otta, accompanied by two destroyers, steamed up the Indian coast, and was east of Wim Kraash by nightfall - though neither carrier knew of the other.

19 May

The South African battleline reduced speed to avoid reaching Ceylon at night - given the risk of submarines and torpedo craft, Falkenburg preferred to strike Columbo in daylight.

Above: Admiral Falkenburg (left) and an unidentified seaman aboard South Africa.

Above: Admiral Falkenburg (left) and an unidentified seaman aboard South Africa.

The Indian battleline hovered off Columbo as Muivah’s scouts attempted to locate the RSAN.

At 0700, scouts from the Mimir re-acquired the Indian cruisers, which were now reversing course and heading back towards Ceylon, having concluded that the RSAN force eluded them. At 0810, Wim Kraash began launching her strike.

The strike arrived at 0948. Seeking to thin out the cruisers, the strike commander split his aircraft against Male and Jaipur. The section attacking Male pressed home their attack, losing two aircraft but scoring two hits that left the heavy cruiser burning from a fire amidships. Jaipur was luckier, and took only one hit, knocking down one attacker.

The cruisers, however, notified Otta of the attack and the direction in which the South African aircraft departed. The Indian carrier began preparing a strike package of eight aircraft, as four others fanned out to look for the South African carrier. One aircraft did arrive over Wim Kraash, but was bounced by a fighter and shot down before getting a message off. The scout’s dejected crew returned to Otta on a dog-leg course, and referees on Wim Kraash confirmed Captain Sakkers’ assumption that he could not shadow an aircraft that was theoretically shot down. This left Wim Kraash aware that Otta was nearby, but not where. Uncertain how Otta would react to the lost aircraft, Captain Sakkers began running south.

On Otta, Captain Baru ordered the strike launched in the direction of his lost scout at 1330. They arrived over empty seas an hour later, and split into two groups, one curling round to the north, the other to the south. The southerly group spotted Wim Kraash fifteen minutes later and attacked; the carrier’s escorts and fighters shot down three, and the fourth aircraft missed. With a loaded strike on deck, Sakkers ordered them flown off, and the nine remaining bombers launched in the direction that their one attacker had withdrawn to.

The South African bombers, accompanied by four fighters, reached Otta at 1418 and made their run, opposed by two fighters. They claimed a bomber and a fighter before being downed. Unfortunately for the Indians, AA fire from the carrier and her lone escort were insufficient to drive off the attack, and two bombs landed on the carrier. Otta’s forward deck was holed and a fire started in the hanger.

The South African bombers returned to their carrier and found it, too, burning - having been surprised by Otta’s second section of bombers that arrived at about the same time as the attack on Otta took place. Two hits on Wim Kraash left her unable to recover aircraft from astern. This gave the carrier the rare occasion to reverse course and recover her aircraft over the bow while steaming astern.

Another South African strike, launched at 1900, managed to finish off Otta, though by now the South African carrier was down to six bombers and effectively reduced to a reconnaissance platform.

20 May

As weather began to degrade around Columbo, the RSAN battleline moved in. The Indian motor torpedo boats attacked, managing to sink the Maroua for the loss of five of their own. Kimberley took a torpedo that left her damaged but seaworthy, and she was detached with one escort to return to Minicoy.

South Africa, Cameroon and company arrived off Columbo to find it undefended from the sea. Engaging the city’s defences at long range, they mission-killed the base by noon and set course to intercept the Indian cruiser forces, now being shadowed alternately by aircraft from Wim Kraash, Mimir, and those South African cruisers so equipped.

At 1550, Mimir fell victim to the land-based AA-3s again, as the two bombers swept in from the north and landed three bombs on the seaplane tender, leaving her seriously damaged.

Come early evening, the Indian battleships linked up with the cruisers as a scout from Wim Kraash circles at a safe distance. Rear-Admiral Falkenburg decided to engage them, and steered on an intercept course. As night fell, Rear-Admiral Muivah, wary of just such a possibility, ordered his formation to increase speed and placed his ships at general quarters. Both fleets’ destroyers fanned out in an arc, attempting to seek out their enemies.

21 May

The Indian and South African forces made contact at 0238, as the G-130, on the trailing port flank of the Indian formation, spotted the Doto, on the forward left flank of the South African screen. Unbeknownst to both Falkenburg and Muivah, the Indian formation had crossed the South African T several minutes earlier. Had the destroyers not encountered each other, the formations would likely have missed each other.

G-130 fired a flare towards Doto and then illuminated itself, indicating to the latter that she was under fire (the self-lighting representing the flash of her own guns, which would be visible to other ships). Sensing an opportunity to surprise the South Africans, Muivah order his force to come round to port on a bearing that would take them towards Doto and, he hoped, the South African battleships.

As Doto and the Libreville fired flares back at G-130 and lit themselves up, Falkenburg elected to maintain his course and ordered his capital ships to hold their fire, so as to avoid revealing their position prematurely.

The light cruiser Lucknow arrived to assist G-130, engaging Libreville. A few minutes later, the Male arrived - and in the gloom was mis-identified by the Doto as Dara Shikoh, Soon after, South Africa and Cameroon joined in. Male was soon under heavy fire and quickly damaged - yet Muivah’s actual battleships continued to steer, undetected, toward the now-visible South African battleships.

At a range of eight thousand metres, the Indian battleships opened fire, Dara Shikoh engaging South Africa, Babur the Cameroon. Falkenburg, despite his surprise, was quick to react, accepting the proximity of the engagement and turning to bring all of his guns to bear. Although the heavier South African shells began to take their toll, the range was low enough that the Indian shells were penetrating as well.

Torpedoes began to leave tubes as the light division commanders struggled to retain cohesion in their commands. Male’s searchlights were the first to be turned upward to the sky - the agreed upon signal that she was disabled - and she was quickly joined by the unfortunate Doto and then other vessels.

The most shocking event came as the South Africa abruptly turned her lights upward at 0317; then, a blinker light signalled over to her sister, “HAVE EATEN GOLDEN TWINKIE. SERIOUS INDIGESTION. GOOD LUCK.”

As the somewhat astonished Dara Shikoh shifted its fire to Cameroon, the equally shocked dreadnought let loose another salvo against Babur. To the credit of the South African command team, there was very little confusion despite the loss of the flagship, and Commodore De Klerk was quick to order a torpedo attack against the Indian battleships.

The two on one battle continued as Cameroon pounded Babur into a wreck but took damaging fire from Dara Shikoh - and then the dreaded red flares shot into the sky.

The flares were the signal to terminate the exercise, and as the warships began slowing, the reason became clear: the Indian light cruiser Jaipur had collided with South African destroyer Agaue. The latter had been part of the force sent to torpedo Dara Shikoh, while the former had been defending her. Finding themselves on a collision course, both had veered west, with only a hard turn on Jaipur’s part preventing her from taking the destroyer right amidships. As it was, the cruiser’s bow had bitten obliquely into the destroyer’s stern on the port side, nearly shearing off the last ten metres of it.

Three men aboard the destroyer were killed almost instantly as the cruiser sliced into the destroyer’s aft machinery spaces. The toll could have been worse, as the destroyer’s aftermost gun had been destroyed - the gun captain, seeing that a collision was inevitable, had ordered his men to run forward at the last moment. Nonetheless, there were also several injuries, some serious, and now the destroyer was fighting to maintain power and control flooding aft. Jaipur’s captain chose not to back away, reckoning that it might actually do more harm if the bow was helping to plug much of the hole that it had created.

As wireless signals went out to the Escartian, ordering her to proceed to the site with all haste, the destroyer Doris arrived on Agaue’s starboard beam and manoeuvred alongside. Heavy lines were thrown across as sailors began to lash the two destroyers together. After a short consultation, additional lines were thrown down from Jaipur and she, too, was lashed to her victim.

Escartian arrived within a few hours and began assisting the Agaue’s crew in sealing off flooded compartments. After an inspection by divers, Jaipur was unlashed from the destroyer and slowly backed away, her bow coming loose from the destroyer in a screeching shower of sparks. After further evaluation, it was decided that Agaue, Doris, and Escartian would proceed to Mumbai, the site of the nearest Indian drydock, once Escartian had finished initial repairs to the destroyer. Jaipur, accompanied by G-120, would proceed to Madras for inspection and repair; though she was in much better condition, the bow was distorted and there were leaks.

Above: Repair Ship Escartian arrives to assist the Agaue.

Above: Repair Ship Escartian arrives to assist the Agaue.

On that note, it was decided that the exercises would be concluded, for the forces were due to make calls at Alleppey and Trincomalee before arriving in Columbo. Concluding a day early would allow for a modest amount of rest before this last bit of sailing and the Naval Symposium itself.

Quoted

But it might be fun. We really need a set of rules to do this if we plan to continue with both the naval excerises and the skirmishes