September 13

RAF Exercises

We arrived at the Headquarters of No 12 Group, Fighter Command at RAF Watnall. We were official observers of Exercise Emperor V, the RAF’s annual full-scale aerial defence exercise.

No 12 Group is providing the fighter element for Blue Forces;

Duxford Sector

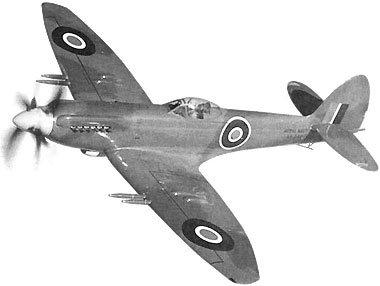

19 Sqn, Supermarine Spitfire F.Mk.III

56 Sqn, Hawker Typhoon F.Mk.I

266 Sqn, Supermarine Spitfire F.Mk.III

609 Sqn (West Riding), Hawker Typhoon F.Mk.I

Coltishall Sector

25 Sqn, Supermarine Spitfire F.Mk.IV

74 Sqn, Supermarine Spitfire II & F.Mk.III

Wittering Sector

32 Sqn, Supermarine Spitfire II

43 Sqn, Supermarine Spitfire II

No 11 Group is providing the fighter element for Red Forces

Hornchurch Sector

81 Sqn, Hornchurch, Hawker Tornado F.Mk.I

1F Sqn, Hornchurch, Hawker Tornado F.Mk.I

41 Sqn, Rochford, Supermarine Spitfire F.Mk.IV

Debden Sector

17 Sqn, Hawker Typhoon F.Mk.I

71 Sqn, Hawker Typhoon F.Mk.I

501 Sqn, Debden, Hawker Typhoon F.Mk.I

RAF Bomber Command allocated the following units as Red Forces;

No 2 Group

Marham Wing

105 Sqn, DH Mosquito B.Mk.I

107 Sqn, DH Mosquito B.Mk.I

110 Sqn, DH Mosquito B.Mk.I

139 Sqn (Jamaica), DH Mosquito B.Mk.I

No 3 Group

RAF Marham

115 Sqn, Bristol Buckingham B.Mk.I

RAF Mildenhall

150 Sqn, Vickers Wellington III

75 Sqn, Mildenhall, Vickers Wellington B.Mk.IV

No 4 Group

RAF Linton-on-Ouse

90 Sqn, Vickers Wellington B.Mk.IV

199 Sqn, Vickers Wellington B.Mk.IV

Here I shall explain the features of the RAF defences of the United Kingdom. As a whole they form an interconnected defence network probably unparalleled in the world and operational since 1938.

The first element is the Radio-Location stations, known to the British as Chain Home and Chain Home Low. These consist of long-range and low-altitude systems respectively of over lapping coverage which extends from Southern Wales to Northern Scotland. The Chain Home Low can detect targets as low at 500 feet Chain Home has a range that extends almost to the Hague in the Netherlands and over Northern France, including the entire Cherbourg Peninsular. The Chain stations report their data back to the Group Headquarters of Fighter Command (Groups 10, 11, 12 and 13) and the central Fighter Command Headquarters at Stanmore. Air Marshal William Sholto Douglas is the current commander of Fighter Command. Each of the Groups of Fighter Command cover a geographical location, No 12 Group covers the central portion of England from Cambridgeshire and Norfolk up to the North Yorkshire Moors and westward as far as Wales. Feeding into this system is a network of Observer Corps stations across the country which fill the gaps between Radio-Location coverage, mainly indemnifying enemy aircraft as the cross the coast to classify them by type and to catch low-level enemy aircraft operating under the effective ceiling of Chain Home Low. The Observer Corps are all part-time volunteers and many of them are ex-servicemen. In wartime they would be formed as a permanent unit of the defence network. The Observer Corps is also split into Groups and Sub-Groups and these regional Headquarters feed the RAF Group Headquarters. Acting on information from Fighter Command Headquarters at Stanmore, which has a national air defence picture, and its local Chain stations and Observer Corps units, the Group Headquarters issues orders to the RAF fighter squadrons and Army Anti-Aircraft units in its area of responsibility. Each RAF Fighter Command Group is further sub-dived into Sectors, each having its own Sector HQ which controls the fighters directly. Therefore during the first day of the Exercise we were witnessing the operations of the Headquarters of No 12 Group, Fighter Command at RAF Watnall. It passed its orders down to the Duxford, Coltishall and Wittering Sectors which directly controlled the fighter sorties using data supplied from the command chain and reporting further data back to the command chain. The entire network is linked by the Defence Teleprinter Network which was built up from 1938 and expanded to twice the size of the civil network.

Britain does not just rely on Fighter Command, most AA units of the Army are now equipped with gun-laying RDF sets and those sets can be used to cue searchlights for night defence.

Current RDF sets in use are;

Chain Home Type 2: since 1938-40, range of 125-195 miles, 42.5-50.5MHz

Gun Laying Type 1: since 1938, range of 28 miles, 54-85MHz

Gun Laying Mk II: new for 1942 for use with 3.7in AA guns with a 10cm wavelength

Chain Home Low Type 1: since 1939 range of 55 miles, 200MHz

Chain Home Low Type 2: since 1940, as Type 1 but deployed overseas

G.C.I Type 1: since 1939, range of 112 miles, 209MHz

Chain Home Extra Low: since 1941, range of 35 miles

Searchlight Laying: new type in 1942 and based on the Gun Laying Mk II

Chain Home Type: new type in 1942, a mobile Chain Home Type 2 for use in remote locations and as reserve sets

The object of today’s exercises was Red Force was to launch a series of bombing raids against central England with Blue Forces defending. We witnessed the Chain Home plots, and those of the Blue fighters intercepting Red formations. There were few standing patrols, the use of early-warning meant that defending forces can be kept at readiness on the ground. With enough warning intercepting formations can be in place in time to catch the attackers and often are keyed in by RDF data ahead of the enemy. Low-level response poses a threat but some patrols were flown to counteract. The use of ambush tactics meant that large formations of Blue fighters could be scrambled to check decisive large Red formations. The Group HQ controlled the battle, directing the Sector HQ as to what squadrons to send and they in turn sent back data indicating which squadrons were ready or were being refuelled and rearmed by the use of illuminated boards. That way any sector, or Group, of Fighter Command can be reinforced by its neighbour. The underground HQs are well protected (we were told we would be safe from 1,000lb bomb direct hits) and inside the plotting room has a large table (the further down the Command Chain the smaller the map and more local the scope) where the operators keep the plots updated, above are the controllers and Army liaison officers behind glass with rows of telephones. They have an excellent view of the map plotting table and yet work calmly separated from the sounds of the bustle below so they can concentrate on the work in hand. Efficiency is key to smooth operations and the staff seemed well-oiled in their work and at times it seemed effortless. All the time information was flowing back and forth across the exercise area via the DTN the system works well under exercise conditions. Such networks we were told exist elsewhere across the Empire.